BigLife salutes Stein and the big life he led. Generations of skiers and mountain town dwellers thank you.

In the late 1950s, the great skier Stein Eriksen had written a book called Come Ski With Me, and that’s exactly what Rolf Sandberg of Fairfield, Connecticut, planned to do. Rolf was 16 years old when the Norwegian superstar won Gold and Silver medals in the 1952 Oslo Winter Olympics. As a teenager obsessed with skiing, Rolf was inspired by the athletic achievements of Stein, but also by the style and grace with which they were achieved. More importantly, Rolf was inspired by a man who often said skiing was his life, and that was a life that Rolf knew he wanted too.

Young Rolf’s yard in Fairfield was more field than anything else, which is to say it was more or less flat. This presented a challenge for the self-described adventurer who was in love with the dream of flying downhill with two long wooden planks under his feet. So he had to create his own terrain. To get enough speed to practice just one turn, he would build a makeshift ramp by stacking wooden crates, pack the transition down with snow, then climb on top, strap on his wooden skis, and glide down into the yard and attempt a right-hander. He would do this over and over again, and success was measured by whether or not he finished standing up. He would repeatedly climb back up and do the same thing, but to the left. Again and again. Up and down, until the sun went down. But linking two turns together was simply out of the question. His determination to ski was not deterred by this small reality, so Rolf taught himself how to ski, one turn at a time.

I first met Rolf on my second day in Utah, back in January of 1993. Like Rolf, when I was a kid, all I wanted to do was ski. East Coasters, my family would take one ski trip a year, usually to Vermont or New Hampshire. The rest of the season there might be a day trip or two to Mohawk or Southington. Most of my ski days until high school and the freedom that came with a teenager’s driver’s license were backyard affairs, on ancient equipment that my brothers and I had picked up at a church garage sale. Out-of-date stuff like leather boots and wood skis with cable bindings. We didn’t care. If it snowed, we’d build jumps in our neighbor’s yard, bust out the old relics, and hurl ourselves off of our makeshift lawsuits-waiting-to-happen jumps. When I got to Utah, I was at the end of my line—a month-long post-grad school ski trip chasing the snow that took me through Aspen, and all the way through to the bottom of my bank account. I had $20 in my pocket when I arrived at the house of Rob DeMartin, a classmate from high school in Fairfield, Connecticut. I thought I might sell my car for a plane ticket home, but Rob called a favor in to a family friend. “Hey Rolf, I have a high school buddy here who needs a job so he can buy ski passes.” I was told to go to Bell’s Silver Creek Sinclair just outside of Park City, and look for a friendly guy with snow- white hair who would meet me for coffee at 8:00 AM the next morning. Rolf was a respected contractor back then, building big houses in Park City, and he made up a job for me because Rob had asked him to.

Rolf graduated from high school in 1958, and straight away enlisted in the Army, as many young men did back then, and when Rolf found out he was going to be based in post-World War II Germany, he was thrilled for the opportunity to travel abroad, even if it meant taking a break from skiing, or at least so he thought. Unlike the backyard turns that never quite had a chance of linking up, a series of what Rolf describes as small life miracles not only kept him skiing, but would lead to a life of skiing.

Stationed in the Bavarian mountains, Rolf found a way to make skiing part of his job. There was an opportunity within his company to try out for ski patrol duty in Garmisch. “Naturally, everyone wanted to do it, because it was skiing, and it sounded like fun, and it got you up in the mountains and away from normal Army stuff,” Rolf recalls. Not many of the soldiers made the cut, however, because it actually involved skiing, a skill few of them had.

That morning of the exam, they loaded up the aerial tram that took them to the observation deck at the top. It was here they were expected to put on their skis and sidestep down to a traverse that would take them over to a small poma lift where they would take the skiing exam. Once on top, Rolf stood shoulder to shoulder with others in his unit, staring down into the valley below. This was no backyard makeshift ramp, and Rolf loved it. Rolf remembers that many of the soldiers took one look at the traverse, then climbed back up to the relative safety of the observation deck without even giving it a try. But Rolf, bolstered by his years of backyard ski school, took the traverse, took the exam, and passed.

After passing this test, it was almost as if Rolf and a select few of his Army buddies weren’t in the Army any more. The officer in charge told them “this is your base now,” as he looked around the mountains. They were outfitted with gear and uniforms, but they were not Army uniforms, they were ski patrol uniforms. For almost the entirety of his two years of military service, Rolf linked turns around a mountain in Germany.

Once Rolf was out of the Army, he took the opportunity for an overseas discharge so he could spend a few weeks bumming around Europe. He traveled to Norway to visit relatives, then back to Berlin to catch an Army plane back to the States. But when he returned to Fairfield, things were different. His childhood friends were locked into new jobs and new lives starting families, and it was as if in the two short years he was in the Army, life had somehow gotten on without him.

He called Frank Wright, an Army buddy from California who had also made the cut in the Garmisch ski patrol, and Frank told Rolf about a ski school out there that was short-staffed. Frank would vouch for Rolf’s skiing abilities to Dave McCoy, the legendary founder and owner of Mammoth, and Rolf was almost certainly guaranteed a job if he could make his way to California, but he had to get there right away. In a matter of weeks since returning from Europe, Rolf was on the move again. He flew to Reno, took a bus to Bishop, and hitched a ride in a VW bus with some locals up to the mountain. Dave McCoy was waiting for him with a job in the ski school, just like Frank Wright promised.

It was in Mammoth that Rolf met his soon-to-be wife Pam, and it seemed like this was going to be the place to settle down and start a family, if it hadn’t been for that one thing that everyone who makes their living in a ski town depends on—that which is inherently undependable, but essential—the snow. During a horrible drought year at Mammoth, there was no snow, and there were very few skiers, which made it tough for the McCoys (who had become friends of Rolf’s) to justify having ski instructors, and as a result, almost everyone on the ski school staff was laid off.

While there was no snow in Mammoth, the ski resorts in the East were getting pounded, so in the span of a week after the layoff, Rolf and Pam made a quick decision to get married, then packed up the car and chased the snow, because that’s where the jobs were. Rolf became assistant ski school director at Mt. Sunapee in New Hampshire for a few seasons, and there was a brief period where Rolf almost gave up on a life of skiing. He now had a young daughter, Kari, and a new baby boy, Rolfie, and he felt he needed to do the responsible thing as a father and get a “real” job. This brought him and his family back to Connecticut for a time. “Back then, a lot of guys I knew were going to work for IBM, big companies like that. But I didn’t have that kind of experience,” Rolf recalls. He started looking at his options, and they all involved a move back west. He had a standing offer to return to the ski school staff at Mammoth, but was spooked about what he would do if there was another drought year. He had a handshake deal to join the ski school in Jackson Hole, but no solid prospects of summer work.

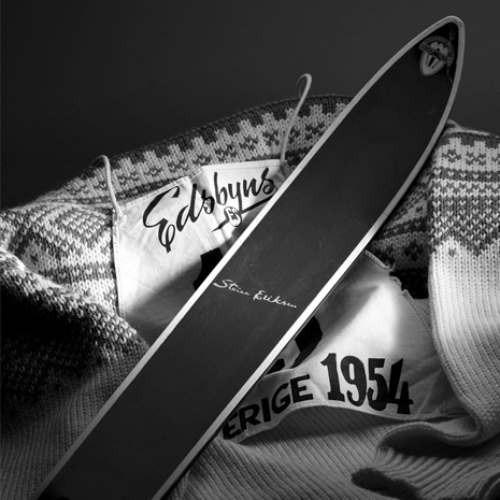

While working part-time in a ski shop in Darien, Connecticut, Rolf heard through the ski industry grapevine that there was going to be a new ski resort opening in the Aspen area called Snowmass-at-Aspen, and that the Snowmass folks had made a deal to bring the legendary Stein Eriksen all the way from Sugarbush, Vermont, to start a new ski school. The ski industry pioneer who relayed that information to Rolf was Nick Hock. You may not know who Nick Hock is by name but if you’ve ever seen a Lange Girl poster from any generation hanging in the dorm room of a college kid, or above the tuning bench at any ski shop, he would be the guy to thank for that marketing coup. At the time, Hock was running one of the ski magazines, and seemed to know everything about anything that was going on at all the ski resorts across the country. Rolf recalls having dinner with Hock, and explaining the dilemma that they had to get out of the East or he feared for his marriage and young family’s well-being, and Hock was adamant: “You must go to Aspen.” That, and the call of Stein, was enough to convince Rolf.

And that’s just how these things go. No job offer, no connections. Just a wing and a prayer and a little bit of good luck.

Once in Aspen, Rolf was determined to track down Stein and ask for a job. He found the small office on the mountain that Stein was using and met a man named Jack Stiles who said Stein was out skiing. “There’s not too many people on the hill today; you can probably find him, if you are lucky.” After skiing around a bit, he recognized Stein in a lift line with another skier, and he skied up, introduced himself, dropped Nick Hock’s name as a mutual friend, and inquired if there were any upcoming opportunities to join Stein’s new ski school. Stein’s reply was an echo from the title of his book, and a foreshadowing of the relationship that would develop between the two: “Why don’t you come ski a few runs with me?”

“Well, sure, thank you,” Rolf said, knowing full well this was probably the only live audition he was going to get, and that if he couldn’t keep up, it wouldn’t matter how many recommendations he had from mutual friends or years teaching at Mammoth on his resume; he was truly under the microscope. The thing is, he remembers Stein being so friendly, and the conversation was more about life in general and not skiing technique, and Rolf was able to ski fluidly and almost forget that this was essentially an ad hoc job interview. A few runs turned into the rest of the day, and as he was about to part ways with his childhood hero, Rolf asked the question, “So what do you think about that job for next season?” Stein looked over at the other skier and paused for a moment, then looked back at Rolf. “Well, there will be a test. But I think if you come next season, you should pass.”

Rolf went back to the Snowmass business office and inquired if they might have any construction positions available, seeing as it was a new resort and no buildings had been built yet up on the mountain. He met a man named Don Davidson who was in charge of getting things done, and Davidson asked Rolf if he was on any sort of time limit. “I need to go pick someone up at the airport, so why don’t you ride along, and we can chat?”

The man they were picking up was George Shaw, a big contractor out of Denver who would be building a lot of the initial buildings of the new resort. Rolf explained that he had just lined up a winter job in the ski school (sort of) but needed summer work to justify moving his family out. It was February 1967, and Rolf was told if he could be back by April, he’d have a job.

Another handshake deal that meant he could pack up the family and head West again.

Rolf loaded his family in the Studebaker station wagon with a homemade trailer in tow and left Fairfield, this time for good. With Pam and their two young children, Kari (3.5) and young Rolfie, who was just 6 months old, they arrived in Aspen in April of 1967. All the handshake offers were honored and Rolf became one of two token Americans among Stein’s 25. the others were mostly Norwegians, a few Austrians, and it probably didn’t hurt that Rolf had a Norwegian name. These were the cream of the crop at the time, and Stein was on the verge of rolling out something revolutionary in this new Snowmass-at-Aspen ski school.

Rolf worked construction all summer, and as the days got shorter and the nights cooler, Stein got the word out around town that he was going to get his crew together as soon as there was snow on the mountain. They had work to do. Rolf recalls that for a couple of weeks before the resort was to officially open to the public, Stein and his 25 were out on skis starting to learn Stein’s progressions and new techniques. Stein wasn’t just gathering a group of instructors to take money from wealthy folks and help them get down the hill. He was establishing a new school of thought on technique, and a system. “Imagine a ski resort doing that today, opening the hill and running the lifts for 25 instructors. It would never happen!” says Rolf.

“I think Stein was a great opportunist in those first few years of Snowmass,” says Rolf. Timing was everything. While everyone was arguing about the right way to teach skiing; the Austrian technique, or the French technique, or the new American technique, Stein’s way was going to teach all the fundamentals, plus make it look good. Style and grace were going to be equally important. “Stein was very tight and particular in what he wanted to see in our skiing, and if you were going to teach it, you were going to have to ski it,” says Rolf. They were drilled on things like perfecting the Uphill Christie, and always finishing the turn with their feet together. “He added the style to the fundamentals.” With his iconic aura, his magnetic personality, and his emphasis on loyalty and camaraderie, Stein made everyone on his crew want to reach for the highest levels, if for no other reason than because that’s how Stein thought it should be done.

“If an instructor was making sloppy turns underneath the lift and Stein didn’t like the way they were skiing, he would relegate them to the lower mountain for a week or so,” says Rolf. “I don’t want to see you skiing above Sam’s Knob until you get those feet together,” he’d say. It was all in good fun, though. He just wanted it a certain way, and, according to Rolf, everyone was inspired and motivated to do it right.

Another thing Stein was particular about was how his crew looked in regards to appearance, and this got young Rolf in hot water with the boss every once in a while.

“Back then, we all wore white turtlenecks under our Norwegian sweaters. Occasionally Stein would grab the top of your turtleneck with his finger and pull it away to have a look.” “Hey Rolf, when was the last time you washed this thing?” And Rolf laughs when he talks about his ski boots. “Back in the late ’60s, plastic shell ski boots were really taking over, but I still had a handmade pair of Hans Rogge leather boots that I had bought when I was in the army. If you wore leather boots like I did, you had to polish them all the time.” The one thing Rolf couldn’t do anything about was his head of hair. Rolf’s wild hair was the Yang to Stein’s impeccable not-a-hair-out-of-place-ever Yin. “Rolf, can’t you do anything with that hair?” Stein would joke. “Well, Pops, what do you think I should do?” replied Rolf. Pops was Rolf’s special name for his boss turned great friend, and it would travel with the two for the next 40 years as Rolf followed Stein to Park City, and then shortly after that, to Deer Valley.

The bond that was formed between Stein, Rolf, and the others from the original Snowmass crew never wavered over the years, although their ranks may have thinned by the passing of time. For many years after they came to Park City, Stein and Rolf would road trip to Aspen once a season for a reunion. The Snowmass folks would welcome the return of Stein for the weekend by rolling out the red carpet. They would have the run of the place, private ski races amongst the old friends, and perhaps by the time the weekend festivities concluded and Stein and Rolf drove back to Park City, they would leave the town of Aspen with a temporary shortage of Aquavit. In Stein’s last years, when health prevented him from making the trip for the reunions, what remained of the Snowmass crew came to Park City to visit with Stein, and they were all there on the mountain on February 4, 2016, when Deer Valley Resort hosted a special celebration of Stein’s life during the FIS Freestyle World Cup event.

As everyone in the ski world knows, Stein passed away December 27, 2015, and the community of skiers around the world have been honoring his influence and character. And his friends have been telling stories.

Rolf mentions a handful of mostly Norwegian names, still alive and back in Aspen, part of that original Snowmass crew. “If you call them, they’ll have stories like mine. I’m just a guy who through good fortune, the right timing, and those small miracles in life, got to call him my friend. He was like a big brother to me.”

Among his friends and those who had the good fortune to meet him, Stein was known as much for his generosity and loyalty as his grace and elegance on skis. “He had the ability to leave everyone he met with something— a joke, a compliment, a kind word, a memory, or a lasting impression. It was as if he always had a small gift for everyone he met.”

We’re going to miss you, Pops.