A few years ago, when my son was in second grade, he was invited to join a group of kids on an overnight trip to Intermountain Bird Observatory (IBO) on the outskirts of Boise, Idaho. At the time, I had no idea what IBO was or what happened at Lucky Peak (home to one of IBO’s research stations), but a parent needed to go with him, so I signed up for the adventure.

Run by Boise State University, Intermountain Bird Observatory is a scientific organization dedicated to banding and studying birds—raptors, songbirds, and owls. Its mission is to impact human lives and significantly contribute to bird conservation through a unique combination of cooperative research, education, discovery of the natural world, and community engagement.

This many years later, our first weekend at IBO still stands out as one of my all-time favorite parenting moments. I could take no credit for it as I lucked into it, but you know what they say—showing up is 90 percent of life. We had invited two of my son’s close friends to join us for the weekend, not knowing exactly what we were in for. It was cold and the camping was the other side of glamping—sharing a tent with three eight-year-olds who have no regard for keeping their camping situation tidy is an experience, to say the least—but even before the long night was over, I was planning another trip to IBO for the whole family.

The IBO experience is three-fold; if you sign up for the overnight option you will get to see the biologists working with raptors in the afternoon, owls throughout the night, and songbirds in the morning. We arrived around noon, made the long and challenging drive up to Lucky Peak (you definitely want a four-wheel-drive vehicle for this trek), and hiked up a hill that overlooks the raptor station. A pair of scientists sat at the top of the hill taking note of the raptors that their counterpart in the raptor shack lured into the net by teasing them with a live pigeon or other such bird that the raptor would naturally prey on. When the lure worked, as it often did, the would-be prey was fine (much to the relief of the youngsters I was with), and the scientist heading up the efforts in the raptor shack would bring the raptor in to record measurements and tag it.

My three young companions and I were able to spend time in the raptor shack with the Research Director at IBO, Jay Carlisle. Watching Jay work the netting system is like watching a captain manning a ship. He’s perched at the front of the shack, looking out at the vast sky and, when he spots a raptor, he handles a netting system with two parts guile and one part grace. Jay’s research focuses on stopover ecology, habitat needs, and conservation of migratory land birds in the West as well as Latin America. And his energy and passion for the work is palpable. He’s a natural with the kids, encouraging them to help with the science of measurements and record-taking.

The raptors are transported from the net to the shack in a can, face down. Transported like this, the birds all remain remarkably calm. Once the measurements were recorded and Jay and his researchers had banded the birds, Jay would encourage the kids to release the birds. Some chose to do so, while others were satisfied to watch. There might have been a red-tailed hawk that pecked at a finger or two, but being that close to these powerful, fast, keen-eyed, high-flying birds left my compatriots (and myself) wide-eyed with wonder and wanting more.

Working in the raptor shack requires patience and quiet. I’m not sure how much time you spend around groups of eight-year-olds, but those are not the first characteristics that come to mind when I think of any eight-year-olds I have known, especially when in a group. But for the hours we spent in the raptor shack, the possibility of being up-close-and-personal with a red-tailed hawk or a Cooper’s hawk or, if we were really lucky, a peregrine falcon, kept the kids quiet. Their curiosity calmed their need to wiggle and giggle. They asked questions, listened, and watched with wide eyes and a sense of connection to the wider world.

In addition to the monitoring and banding station at LuckyPeak, IBO operates long-term stations on the Boise River, at Idaho City, and at Silver Creek. Their work helps us understand more about the migration patterns of birds and the way human activity impacts their movements and the overall health of bird populations. Each researcher who works with IBO has their own field of research. Some biologists have taken a circuitous path to their current work. Rob Miller joined IBO in 2009 as a volunteer after a 21-year career at HP. His volunteer work led him to earn a master’s degree in Raptor Biology. Rob heads up the long-term study of goshawk ecology within the Intermountain West as well as Project WAfLs, an eight-state survey of short-eared owls.

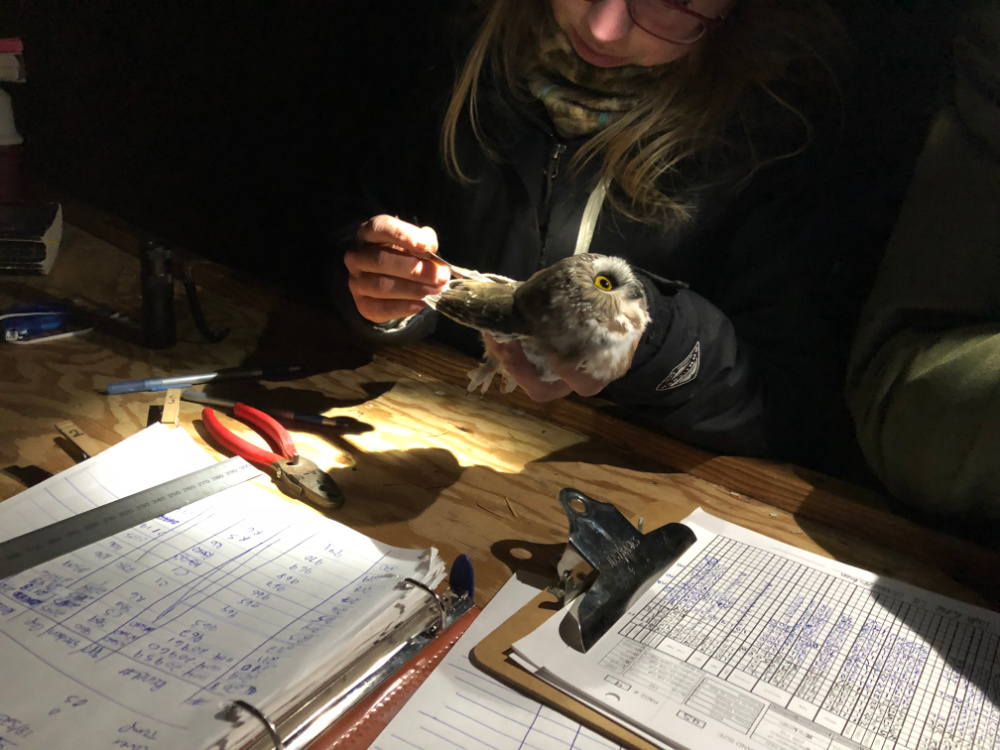

Speaking of owls, following an afternoon of raptors, the focus turns to the nocturnal world of owls. The scientists who study the birds who fly and hunt and hustle during the day settle in for dinner and bed, while the biologists studying owl behavior and health start emerging from their tents, ready for their “day” to begin. Around dusk, a speaker system around camp starts to play owl calls and we learn that there is a system of netting set up throughout the forest on Lucky Peak. If the kids were inclined, biologists would walk through the forest every hour to collect owls and bring them back to the main research hut where their colleagues would be waiting to measure, weigh, band, and record any noteworthy detail. My small companions were intent on going every hour, so we set my alarm and committed ourselves to a sleepless but incredible night.

We walked the trails with the researchers—amazed to see how many owls were caught in the nets and how small they were. Most of the owls were Flammulated and Saw-whet owls and they would fit in the palm of your hand. To transport the birds, we put them in small bags and pinned them to our shirts and walked our collection back to the hut. From around 8pm to the wee hours in the early morning, we did this every hour on the hour. And it never got old. We were visitors in this nocturnal world, and it gave us all—adult or child—a new perspective on the world and the wonderful creatures that roam it. The kids who were awake each hour would release these small owls after they had been banded and recorded, honored to play a role in the lives of the owls and also in the work to protect owls and their habitats.

After a little, and I mean a little, shut-eye in between owl work and full-swing morning, it’s songbird time. The songbird work mirrors the owl work in many ways, just with daylight. We would collect the songbirds throughout the netting system in the forest and carry them in bags back to the research hut for banding and recording. Then the kids would release them. The weekend we were there, IBO logged a record number of songbirds.

Research is at the core of the IBO mission, but so is sharing their passion for this research and for the birds they serve with volunteers, student groups, and anyone interested in taking the time to visit and see first-hand research at work. IBO’s banding stations form the foundation of their monitoring work and they partner with organizations throughout the Intermountain West to monitor and conserve breeding bird populations in six states.

After a morning of songbirds,I drove back down Lucky Peak, poised to head home, with three exhausted eight-year-olds who couldn’t stop talking about the Cooper’s hawk they released or the Saw-whet owl that pooped on their finger, or the Townsend’s warbler’s colors. They each staked their claim on a favorite experience or moment, all the while sharing in the wonder of the world of birds.

SHARING A PASSION FOR BIRDS

Painter and former Ketchum Parks and Recreation wrangler of kids for an afterschool program called “The Wreck,” Poo Wright-Pulliam has long organized visits to IBO for groups of her Wreck students. She is the reason I made the trek with my cohort of three. She says, “I love to share IBO with anyone who shows an interest in birds because seeing the birds in-hand can be life-changing. A love of nature and learning begins here; the staff is so helpful for kids and adults. My Wreck kids always said, ‘IBO is the place to go!’ and I couldn’t agree more.”