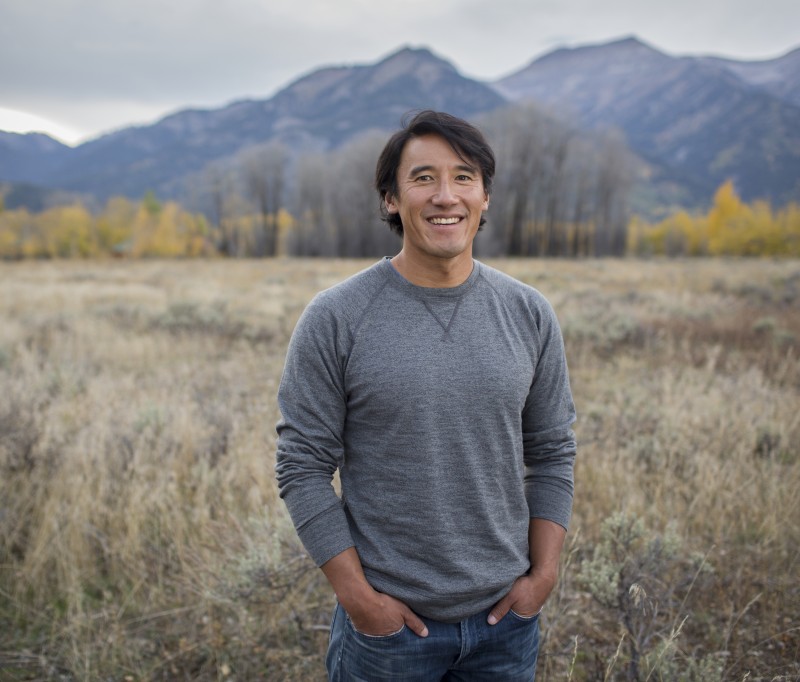

In 2008 three world-class mountaineers set out to climb the Shark’s Fin, one of the major unclimbed testpieces on the remote Himalayan peak of Mount Meru in India. The group consisted of Conrad Anker, a preeminent alpinist from Bozeman, Montana, and leader of the group, and Renan Ozturk, a big-wall phenom and burgeoning cinematographer. The third member, Jimmy Chin, is a beguiling specimen of tenacity and strength, and the main energy center behind their award-winning and Oscar®-nominated documentary, “Meru.”

Over the last decade Jimmy Chin has distinguished himself as one of the most prominent American adventurers and photographers. He’s been a professional athlete for The North Face since 2003, traveling the world as a skier, climber, and chronicler of seldom-reached corners of the globe. He’s got a stable of sponsors, he’s been the face of an international Revo ad campaign, and he made Outside’s cover as “Explorer of the Year.”

Expanding his skill set into moving pictures didn’t hurt either. Working alongside veteran mountain filmers and directors such as Rick Ridgeway, David Breashears, and Stephen Daldry, Jimmy’s cinematic education took place primarily on assignment. A preternatural eye for narrative can be seen in his work, which has appeared on ESPN, National Geographic Channel, and in innumerable projects for television, film, and commercial. And with a tireless work ethic, pan-athleticism, and deferential charm, it’s no wonder that JImmy is only getting busier.

Released earlier this year, Meru is a story of rise, fall, and redemption in the big mountains. Peppered with interviews of the climbers and their families, along with dizzying footage from their attempts in 2008 and 2011, the film won the Audience Award at Sundance and launched Chin onto the grand stage of documentary filmmaking.

The film opens with the wearied climbers sitting captive on a portaledge, huddled in down jackets zipped to the nose, wind and blowing snow battering the tent walls. Wisps of steam puff out their nostrils with each short breath. A thin floor of aluminum stays and nylon is the only thing separating them from the cold Himalayan abyss below their temporary home at 20,000 feet. It’s a sobering image of the desolation climbers face in their quest for glory. At a glance, the scene would lead anyone to believe Jimmy is a stone-faced Ahab, monomaniacal, chasing the white whale into alpine oblivion. And that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

I met Jimmy about 15 years ago in Jackson, Wyoming. He was like any other late 20-something who’d eschewed a more traditional path in life for a chance to romanticize the mountains. He’d already lived as the proverbial dirtbag climber—an enthusiasm that put him on non-speaking terms with his father. “You’re not taught in school to live in a cave in Yosemite and rock climb,” he admits. “Those are still hard years for me to justify, and I struggled with that because there was doubt everyday.”

In Jackson Jimmy lived in an apartment with other ski bums. He smoked weed and got after it in the mountains. I’d see him on a peak, in the backcountry, or at a neighborhood BBQ. But he was also the prime example of a sandbagger. Lighthearted and cheery in conversation, Jimmy was pony-tailed, humble, and silly—belying any notion of hardman climber. But behind the fog of reefer and casual joviality lived a razor-sharp determination that has been in him since he was a kid.

Let me qualify that. One night in the early 2000s there was a fundraising party for our independent radio station KHOL, a big night in the spring off-season where everyone of our ilk came out to drink and support homegrown radio. Jimmy was apparently a little tired that night and not quite his usual buoyant self. What only a few knew was that he’d gotten up early that morning, and hiked and skied (solo) the Grand, Middle, and South Tetons in a single push. In 10 hours. Car-to-car. While credit should be given to Mark Newcomb for being the first to complete the task, let it be known—it’s not a light jog around some silver lake. I think that’s when a lot of us around Jackson started to realize that Jimmy wasn’t fucking around.

Let’s back up. Twenty-five years ago, Jimmy Chin was like any other Midwestern kid growing up in Mankato, Minnesota. Sort of. His parents had fled China in the 1940s during the Communist Revolution to begin a new life in America. Despite a fresh start in the heartland, Jimmy’s father still retained his stringent military upbringing and instilled fiercely austere virtues into his son. “My dad was always about being tough,” says Chin. His father enrolled him in competitive swimming and martial arts throughout the majority of his childhood and adolescence. He could also be pinned to the proverbial violin lessons that filled many mornings. For all the rigorous demands set by his father during the formative years, Jimmy now readily admits that [some of] his father’s draconian approach to parenting prepared him for the challenges and successes he has faced as an adult. “And I get it now,” he says. “You get to choose what to instill in your children. It was about respecting elders, loyalty to friends, and integrity.”

It has served him well. Much of Jimmy’s success in the mountains can be traced directly back to those earlier days in Minnesota. “You learn to push yourself,” he says. “Martial arts and swimming taught me a lot about training and pacing. It was just a part of my upbringing. I didn’t know otherwise.” Because both are pursuant to the perfection of movement, it should come as no shock that Jimmy would carry those lessons learned from his father’s strict tutelage. Like martial arts, mountaineering can be reduced to simple practices. Move with purpose—a major tenet of swift and deliberate mountain travel.

The last six months of Jimmy Chin’s life can be measured by the amount of ink he’s received for the movie. In fact, there’s an artist’s rendering of him and his wife Elizabeth Chai Vaserhelyi (she co-directed the movie with Jimmy) in a recent issue of The New Yorker, if that gives you any idea. After the fanfare at Sundance, Jimmy’s been jetting across the U.S. at a breakneck pace, promoting the film alongside Chai, appearing on talk shows, film panels, and filling entire days with interviews, including mine.

Jimmy will be the first to admit he doesn’t like being in front of a camera. “It’s the worst,” he says. “Part of it is probably vulnerability. Anyone who’s had to shoot me knows I’m a terrible person to shoot because all I want to do is direct. Maybe I’m a control freak.”

This is odd, as mountaineering always has inherent uncertainty, kryptonite for a control freak, which segues the conversation invariably to risk. For extreme athletes in mountain sports, risk is a hot-button topic. Why do you do what you do? You can die. “We try to approach it in the movie,” says Chin. “And we don’t try to answer it. We just put it out there.” Which is clever. Risk is a loaded term and everyone approaches it differently. “We spend so much time worrying about risking too much, and much less time about risking too little,” says Chin. “Maybe we’re [mountain athletes] wired differently being on the edge more, but risking too little is the greatest risk of all. To not fully live because of fear is not what I consider a life well-lived.”

In 2002 Jimmy went to Mount Everest to shoot Stephen Koch try to pioneer a new route via the Japanese to Hornbein Couloir on the north face without the help of supplemental oxygen. They didn’t complete their objective, but they proved there is virtue in failure. At the time, Stephen was gunning to be the first snowboarder to ride the Seven Summits. They could’ve sought out a relatively more conservative line to better their odds at success, but instead they took a risk to raise the bar of high-altitude ski mountaineering and came up short. That’s how it goes above 8,000 meters. For Stephen it would mark the end of an epic journey—one that deserves respect—but for Jimmy it was simply training that would take him back to Everest in 2006 where he made a successful ski descent from the summit with fellow Jackson residents and The North Face athletes Kit and Rob Deslauriers.

Precision and timing pay off in climbing and skiing. But Jimmy is by no means immune to the pitfalls of mountaineering. Between trips to Meru, Renan and Jimmy were working as athletes/cinematographers for The North Face, as well as their own production company Camp4 Collective. Renan and Jimmy experienced separate beat-downs that nearly ended each of their lives.

While on assignment in Wyoming, Renan was skiing outside the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, when he tumbled over some thinly- covered rocks and cracked his skull wide open. Drenched in blood, he was flown out of the mountains and went through an enormous amount of rehabilitation, which viewers experience in the film.

Four days later, with Renan’s condition fresh in his mind, Jimmy was working with professional snowboarders Jeremy Jones and Xavier de la Rue in nearby Grand Teton National Park. It was afternoon and the sun was heating the south-facing slopes. They were making a descent of a now-popular run called “Four-Hour Couloir.” Jimmy triggered an avalanche, which engulfed him immediately, tumbled him nearly 2,000 feet toward the valley floor, and buried him to his waist. He shouldn’t have survived. Miraculously, he wasn’t injured. But a second avalanche soon followed and pummeled him in his place, wild snow smashing into his pinned torso. Again, he managed to escape serious injury. By day’s end, his body was beat up and bruised, but otherwise okay.

Getting shut out on big climbs, averting death, and suffering life-altering injuries is a constant presence in mountain sports. So how does one transcend such near misses? “I learned before those things, which allows me to get back on my feet,” he says. “I had my ass handed to me a lot as a kid competing in martial arts. I was always competing—good days, bad days. I’ve grown enough to follow through on some of the greater successes.”

I wanted a second opinion. So I called Jeremy Jones, a professional snowboarder who has made a career of climbing and riding some of the most remote and technical lines in the world. He also happens to be a friend of Chin’s.

Does he think that failing in the mountains can be a good teacher, a good motivator? “I don’t like that term,” Jones says. “Failure to me means you’re dead and not coming home.” He has a family, and he knows that uncertainty and risk are ever present in the mountains. “What I’ve been working on mentally is studying the act of turning around,” says Jones. Like Jimmy, he goes into a project prepared with total commitment. “But when the switch flips, and the acceptable risk becomes too much, you need to be able to make a 180° and walk down without a care in the world. To move fluidly between these two states is the art of doing serious projects in the mountains.”

We see it in “Meru.” The trio spent 17 days on the route, and gave all that they had on the first attempt, only to turn around 100 meters from the summit. To the professional climber, I can only imagine that the sting of defeat, when it’s so close, is spectacular. But it’s certainly not failure, as Jones is quick to point out.

Jimmy and Chai now have a toddler and are expecting their second child. He knows the game changes when kids are involved, understands how they play a part in making decisions, and what a difficult balancing act that is among his peer group. “As a parent I want to set a great example for my children, and I need to be around to set a good example. But the idea that we have control over it all… I think we’re kind of fooling ourselves.”

At 42, Chin is experiencing life at full tide. He’s working nonstop, raising a daughter, and sees the future with eyes wide open. “I still have that same drive and ambition to climb in the big mountains, and we’ll see if that happens. There are so many other aspects in life too, whether as a filmmaker, a photographer. There’s tons of risk in the creative field too. But I also understand what carries weight: your friends whom you’ve known for 20 years and your family. I’ve just been doing what I’ve been doing, some of it is cheesy, and I go through the motions. But at the heart of what I’m doing, it is the same as anyone.”