Open the green box on the mantel above my fireplace; it’s near a pair of vintage skis and twinkling string lights, reminiscent of swirling snow. A sheaf of collected ski resort trail maps is stuffed inside the box. Flicking through the maps rekindles fond memories and the joy of many winters spent etching ski tracks atop those beautifully rendered mountain flanks. The maps contain routes to a chionophile’s treasure: rugged landscapes, groomed corduroy, powder snow, brisk air, cold cheeks, and the ineffable joy of sliding down frozen water.

In collecting these maps, I’m definitely not alone. Most devoted snow sliders have a horde of trail maps stuffed somewhere close. Find them in drawers, jacket pockets, or suspended on the fridge. Instead of boy bands or Leonardo DiCaprio, the walls of my childhood and teenage years were plastered with ski maps. There are just two similarities between all these artistic relics: the ski trails snaking through timber and the subtle signature of the artist. Usually tucked beneath a band of cliffs or nestled in a cluster of pines, the watercolorist’s insignia contains three distinctive Es and an M leaning precipitously to the left, reminiscent of the mountains so accurately illustrated. The cartographer behind these wintry treasures? A man named James Niehues.

The spidery scrawl of Niehues’ signature is familiar to those with a passion for skiing or snowboarding. Since 1987, Niehues has kept busy, crossing five continents and painting nearly 200 ski area trail maps. If you’ve traveled to an unknown ski area and gazed at a map to orient yourself, chances are that each pine tree, larch, or birch was hand-painted by Niehues.

Niehues, or Jim as he prefers to be called, didn’t embark on this phase of his career until his 40s. While looking for work in the Denver area, Jim stopped by the office of legendary illustrator, Bill Brown, to see if he needed help with any projects. Bill had lead time on a commission to paint the backside of Mary Jane at Winter Park and gave Jim a shot. Winter Park was pleased with the job and from there, Jim submitted updates for a handful of Brown’s clients with older maps. Before long, Jim had his own commission to paint Boreal and Soda Springs, maps still in use today. Of his career shift, Jim humbly admits, “I’m a farm boy from Colorado. I don’t have any formal art training. I learned on the job.” Subsequent assignments from Vail and Jackson Hole solidified Jim’s unexpected trajectory.

Unfolding a Niehues trail map reveals each mountain in conditions optimal and supreme. It takes little effort to visualize stacking powder laps bathed in the light of golden hour. “I like to show the mountain at the time of day when the shadows are just catching the snow,” says Jim. Unhampered by crowds, bad weather, rope lines, or traffic, the splendid scene beguiles the viewer, reviving past memories or indulging new daydreams. Jim’s mastery of perspective allows him to distill the luminous beauty of each mountain’s facets into just one or two panoramas.

My first connection to Jim’s work is lost in the passage of many winters. I grew up in Utah with a father employed by Snowbird, and family never bothered travelling elsewhere for skiing. I spent my formative years poring over FREEZE magazine and sending off letters to ski areas with self-addressed envelopes imploring them to send me trail maps, please. In stark contrast to the powder pioneers who flocked to Utah from afar, my skiing experience did not extend beyond the Wasatch Range; the maps arriving by mail expanded my imagination.

Each map, freshly delivered by the mail carrier, was immediately scrutinized for that sloping, idiosyncratic signature. Years later, after joining my university’s alpine racing team, I finally skied beyond the borders of Utah. My map collection rapidly expanded while traveling with the team each weekend: Crystal Mountain, Mission Ridge, 49 Degrees North, Mt. Hood Ski Bowl, Mt. Ashland, Silver Mountain, and Steamboat all joined the pile.

Traversing between Washington and Utah during college breaks, my best friend Julie and I would collect new mountains: Stevens Pass, Sun Valley, Jackson Hole, (which we incidentally learned is not along any standard route between WA and UT), and Brundage Mountain. Among the many maps I salvaged, that same signature appeared, camouflaged into the foreground. And I would always wonder… How could one artist be so lucky to get these assignments, traveling the world and churning out gorgeous hand–painted maps for all these mountains and their many visitors?

With adulthood came a new position in the ski industry, one that happily required travel to ski resorts across the U.S. and Canada. I became increasingly reliant on trail maps to avoid disorientation upon all the unknown slopes. After a week of use, I’d stow them in that green box with considerably more wrinkles than those I applied for by snail mail or collected on the racing circuit. The further afield I went, the more I felt at home, because the familiar sight of intricately painted and incredibly accurate trees, chutes, peaks, and that enigmatic signature accompanied each journey. These maps became the mechanism for how I formed and kept memories on each new mountain.

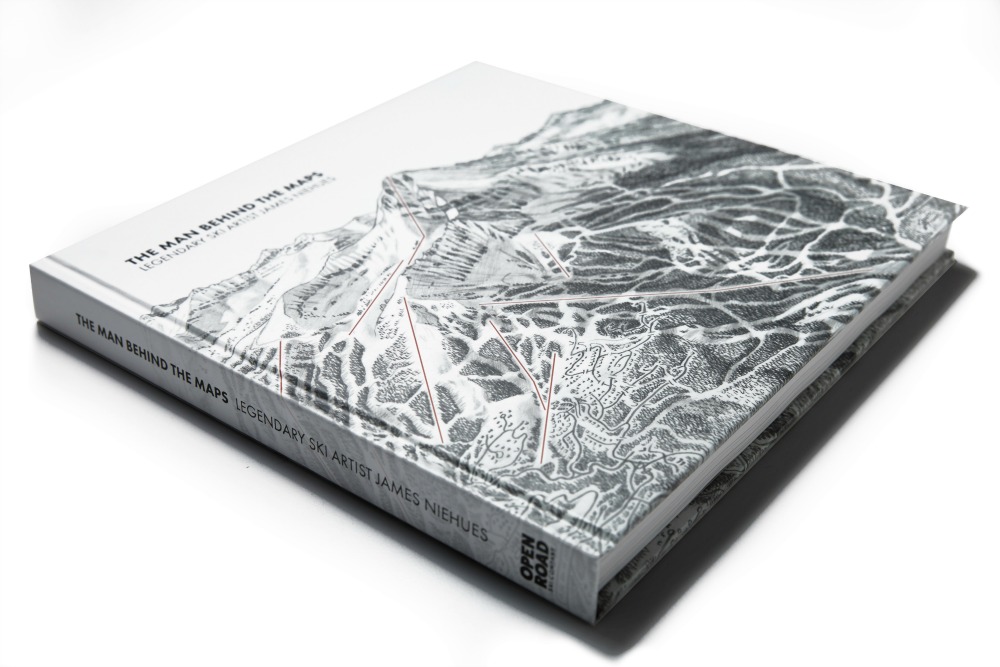

Last November, an algorithm on social media revealed a Kickstarter project in need of funding, James Niehues: The Man Behind the Map. A moment decades in the making, at last I learned about the man who helped me maneuver down mountains. Within minutes of scanning the website, I had pledged a donation and ordered his book, a compendium of over 200 hand-painted ski resort trail maps.

With the book purchase, the opportunity to finally patronize the artistry of Niehues somehow felt proper. For years, I’d amassed his free, portable works of art. Collecting and admiring the maps had enriched my life as a skier and I mulled over how I could further support the legacy of Niehues’ work or even speak to the legend himself.

Days after my impromptu book purchase, I was dialing Niehues’ phone number to interview him for a profile on behalf of Ski Utah magazine. A soft and kind voice answered the line. “Call me Jim,” he quickly added after our initial greetings. At the time, the momentum of pledges rolling in to support his book project was rapidly snowballing. Modest in his reaction to the community’s enthusiasm, Jim confessed, “I don’t have proper words for it. It’s extremely gratifying to know that there are people out there who appreciate my work and will put money up front to buy this book. Mind–boggling. I’m very humbled by it.”

Jim is an unlikely icon for skiers and snowboarders, and in part he failed to comprehend his contribution to the community because he’s been so busy traveling and churning out maps for the last three decades. Always looking forward, as Jim expanded his portfolio, tackling Vail and Jackson Hole early on, he perfected his natural talent for manipulating spatial relationships. The process Jim developed and continues to use imparts his maps with a strong sense of realism, making them both beautiful and useful. His procedure is so laden with subtlety and expertise that no computer or software program could replicate the final product.

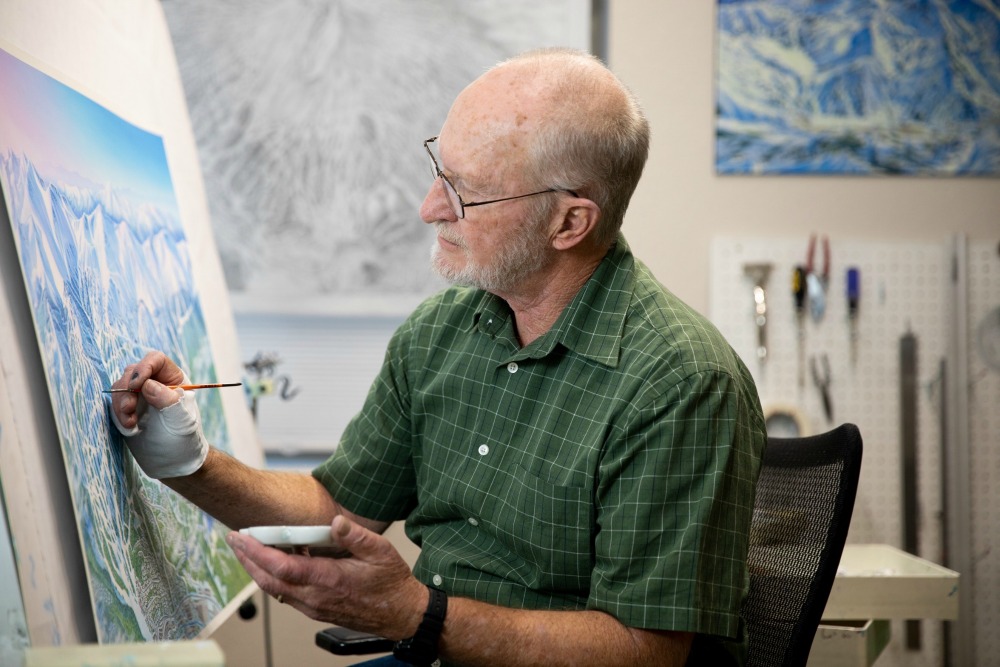

Painting a map begins with Jim snapping countless photos of the mountain on an aerial flight to help him interpret the relationships between contrasting aspects. This is Jim’s favorite part of the process, he explains, “I love the flights. It’s so inspiring to get up in the airplane and fly over the mountain. It certainly is amazing.” As he says this, I can hear him smiling on the other end of the line. Jim will then gather old trail maps, photos, site maps, and satellite images. All this data informs his ability to construct a coherent panorama for resort guests.

Jim then commences with a pencil sketch, working closely with resort personnel for feedback. Jim executes hundreds of minute decisions to employ crafty tricks of perception and shadow. He compares the work to a puzzle, figuring out where and how all the pieces fit together. When his pencil sketches are approved by the resort, he creates a large watercolor proof of the map by projecting his sketches onto canvas and painting over them, working from the top of the mountain down to the village base area or town below. Closing in on his 200th resort, Jim is now wrapping up projects with Mt. Bachelor in Oregon and Sun Peaks, British Columbia. “My calendar is packed, as full as I want it. And this year it snowballed. Maybe I’ll retire next year,” Jim wistfully says, and then adds with a chuckle, “It’s not really a job, it’s a passion!”

Fast–forward four months and I’m improbably standing next to Jim at Alta Ski Area, peering up at the monolith of The Devil’s Castle. He’s in Utah to film a short video for Ski Utah that I’m producing. To see Jim blinking in the sunlight, admiring the view with his kindly smile, I forget that I’m in the presence of a master landscape artist. His enthusiasm for the scenery is genuinely infused within each map. Jim wanders over to a large billboard featuring a map he updated for Alta in 2015 and begins describing his favorite aspects of the mountain. With a sparkle in his eye, I watch him scrutinize the landscape with delight, pointing out defining features and marveling at the scene looming above us.

Over dinner at the Alta Peruvian Lodge, Jim once again expresses disbelief at the success of his book launch, which ultimately clinched the title of best funded Art & Illustration Project in Kickstarter history. Jim’s humble appreciation for his fans is heartfelt; it was an honor to spend the day viewing classic lines at Alta through his eyes.

Thanks to Jim’s legacy, a trail map is a free, portable, lightweight, and useful work of art that fits in your jacket pocket. Our identities as skiers and snowboarders are folded into the creases of these miniature landscapes. Says Jim, “I work hard to make sure each piece is a useful guide to the resort it depicts, that it gives you a feel for the mountain and helps to keep all the memories alive.” jamesniehues.com